In 1518, a woman named Frau Troffea began to dance uncontrollably in the streets of Strasbourg. Within weeks, hundreds of men, women, and even children, were caught in a collective dance frenzy. To contain the chaos, the baffled city authorities consulted physicians, who blamed overheated blood. Their remedy? Movement medicine: more dancing to expel the excess heat. Musicians were hired and the marketplace was turned into a giant dance floor. As bagpipes and drums filled the air, crowds gathered to witness the strange spectacle. A whisper spread that the dancers were cursed by Saint Vitus for their sins.1 Fear crept through the crowd: who among them was without sin? Soon, new limbs twitched and swayed, drawing more into the viral dance.

When the dance cure failed, the authorities banned music and dancing, but it was too late, some 400 people were reportedly dancing, with several collapsing and dying from exhaustion. In desperation, the city officials turned to the clergy. They led a first group of dancers on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint Vitus for yet more dancing. This time, however, it was a sacred dance. The tormented dancers entered a consecrated space, thick with incense and resounding with Latin incantations. They had to wear red shoes, sprinkled with holy water and marked with crosses of consecrated oil.2 The ritual worked miracles, and soon a long procession of dance maniacs was led to the shrine for healing.

Many of us learned in school how the Black Death, or bubonic plague, swept through Europe, killing up to half the population. But fewer know that another, more mysterious epidemic followed in its wake: the dancing plague. This plague caused people to dance uncontrollably for days, sometimes weeks, until they collapsed from exhaustion. The dancing plague or dancing mania is often treated as a historical footnote – a strange blip in our timeline.3 Unjustly so, as reports of these manias span nearly a thousand years, from the 7th to the 17th century, and could sweep from town to town like dancing wildfire. Even in their own time, witnesses were mystified by the events. Chroniclers described how dancers would shout out “Friskes” or “Frisch” and concluded these outcries must be the names of demons. But were they? What was going on? Was this a case of collective madness? A drug-induced dancing delirium? Or was it perhaps a secretive religious sect orchestrating ecstatic flash mobs?

Mansplaining The Inexplicable

A few years after the dancing plague struck Strasbourg in 1518, the Swiss physician Paracelsus discussed the dance manias in his writings. Paracelsus was an intellectual rebel. He rejected religious explanations, such as divine punishment, and speculated about psychological and medical causes. His conclusion was that the dancing manias could either arise from “the imagination” or from the cryptic “laughing veins” where a spiritual force in the body could “tickle” people into joy and dance.4 In the case of Strasbourg, however, he had a more mundane explanation. He blamed a group of women, starting with Frau Troffea, for faking the dance fever to spite their husbands. Others, he claimed, joined in out of religious superstition. “Many people came to believe in this so strongly,” he wrote, “that the dancing was recognized as a real illness.”5 To assert his rational authority, Paracelsus cast himself as the voice of reason and the dancers, especially the women, as hysterical, manipulative, and gullible.6 His theory of the laughing veins did not stand the test of time, but as we shall see, his psychosomatic description and misogynism endured in other guises.

As science became the dominant framework to explain mysterious phenomena, scholars continued to search for medical and psychological explanations for the dancing plagues. In the 1950’s, the Swedisch scholar Louis Backman argued that ergot poisoning was the culprit. Ergot is a toxic fungus that infects grains and can lead to hallucinations and convulsions.7 LSD is in fact derived from ergot, so was the dancing plague a collective bad trip? Not likely. Ergot poisoning can lead to permanent disability or death, while most dance maniacs recovered. Outbreaks also tended to occur in midsummer, not in the colder months when contaminated stored grain was eaten.8

With no clear medical cause, scholars now argue the dancing outbreaks were psychosomatic in nature. Today, the dancing plagues are often cited as a textbook example of a Mass Psychogenic Illness (MPI) – commonly known as mass hysteria. We have all experienced how contagious laughter can be in a group. The MPI theory contents that physical symptoms like fainting, convulsions, and indeed uncontrollable laughter, can spread among people, especially if this group is under distress and has a shared belief about the symptoms. Paracelsus had already touched on this centuries ago, suggesting that a strong belief in divine punishment made the dancing feel like a real illness. Mass Psychogenic Illness sounds like a medical diagnosis, which it is not. It is a description of a set behaviors scholars still cannot fully explain. Whether MPI is a valid diagnosis or an ornate label that masks more than it reveals, like the “laughing veins” before it, remains to be seen. But labeling the behavior of marginalized groups as demonic, pathological, or irrational has often served to uphold power, not truth.

European colonizers and missionaries, for example, denigrated the ecstatic dance practices of Indigenous peoples as primitive, hideous, or demonic, and proceeded to suppress these practices where they could.9 Below are two examples that come from Barbara Ehrenreich’s illuminating book “Dancing in the Streets”. The first is a quote from a Jesuit missionary among the Yup’ik people of late-nineteenth-century Alaska. He wrote:

“I have great hopes for these poor people, even though they are so disgusting on the exterior that nature itself would stand up and take notice … In general their superstitions are a fearful worship of the devil. They indulge profusely in performances and feasts to please their dead but in fact to please and corrupt themselves, in dancing and banqueting.”10

Imagine the Jesuit’s shock if he saw his descendants dancing barefoot in an Ecstatic Dance, their sweaty bodies shaking to the primal beat of a drum and gathering afterward to enjoy a potluck together.

In the mid-nineteenth century, a Presbyterian missionary found black Jamaicans engaged in what they called a Myal dance, and rushed out to stop them, only to be told that the dancers were not, as he supposed, “mad.” “You must be mad yourself,” they told him, “and had best go away.” 11

The questions “who is mad?” and “who gets to decide who is mad?” are highly relevant here. A pivotal moment in the history of psychology illustrates the importance of these questions. Early in his career, Sigmund Freud worked with women who suffered from “hysteria” — a catch-all label, covering everything from emotional instability and sexual impulsivity to fainting, convulsions, and paralysis. Women have received this diagnosis since antiquity. The Greek word hystera (ὑστέρα) means "womb", as Greek physicians believed the uterus could “wander” through the body causing physical and emotional disturbances. Up until Freud’s time, women were believed to be physiologically unstable and thus prone to irrational behavior.

Freud’s work and research with hysterical patients led him to a new and shocking conclusion. He deduced that many hysterical symptoms stemmed from early childhood sexual abuse, often by a male family member. It was a highly controversial claim that rocked the morally uptight and patriarchal Victorian society. Many of his patients came from respected households, and he implicitly accused reputable men of incest and abuse.

Perhaps Freud’s conclusions could have sparked a Victorian MeToo moment, or more likely, he would have been ostracized and forgotten. We will never know, because not long after publishing his theory of real sexual trauma, he publicly denounced it, and instead argued the abuse stories were the result of unconscious, repressed desires – the imagination would Paracelsus say. This reversal marked a turning point in psychiatry: a groundbreaking recognition of systemic trauma was replaced by a theory that relocated the problem into the mind of the female patient. And instead of men getting arrested and strict social norms reevaluated, women were hospitalized.12

Childhood trauma remains under-recognized, even though it lies at the root of many mental health conditions, writes Psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk in his seminal book “The Body Keeps the Score”. In a 2024 interview, he is perplexed by the reluctance of the medical community to fully acknowledge the profound and pervasive impact of trauma. When the root cause is overlooked, he argues, treatment often misses the mark. Instead, van der Kolk advocates alternative therapies that help expand the narrow, survival-focused worldview of traumatized individuals. This includes psychedelic-assisted therapies such as MDMA, as well as embodied practices, like drumming and dancing, that foster connection with the self and others and support the body in processing what the mind cannot articulate alone.13

Dancing into XTC

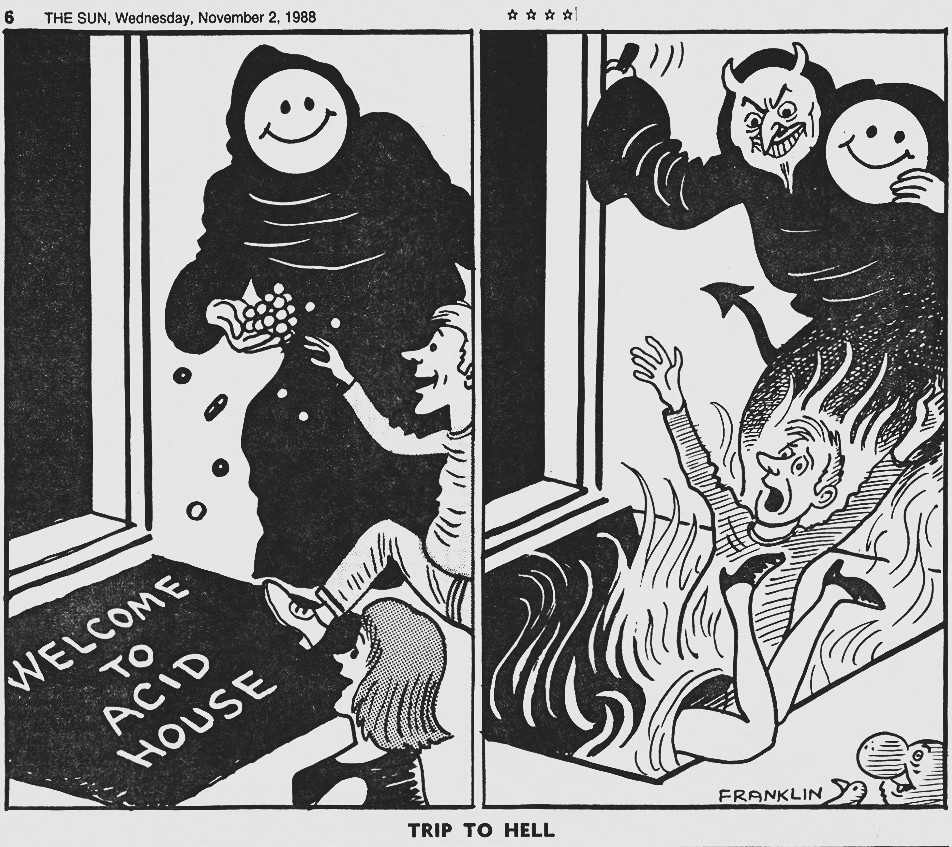

When Acid House hit Britain in the late 1980’s, the tabloids whipped up a moral panic about the massive dance events and the new party drug XTC (MDMA) with headlines like: “£12 TRIP TO AN EVIL NIGHT OF ECSTASY!” (The Mirror 1988), or “SPACED OUT! 11,000 youngsters go drug crazy at Britain’s biggest-ever Acid party (The Sun, 1989)”. These underground events were grassroots organized, and seemingly out of nowhere, thousands of young people could gather in a field or empty warehouse to dance for days.14 There were incidents and deaths, mostly due to overheating and dehydration, but these rare casualties pale in comparison to the injuries and fatalities from a typical alcohol-fueled night out. In fact, we now know that MDMA is significantly less harmful than substances like alcohol, tobacco, or cocaine.15 Still, tabloid fearmongering thrived. The Sun’s columnist and doctor, Vernon Coleman, warned readers:

Most Ecstasy users get flashbacks – and they can happen up to six months after. If you get one in the wrong place, you could kill yourself. For example, you may try to stop cars by standing in the road. There’s a good chance you’ll end up in a mental hospital for life. If you’re young enough there’s a good chance you’ll be sexually assaulted while under the influence. You may not even know until a few days or even weeks later.16

Notice how the cartoonist invokes the medieval trope of the Devil to scare the readers.

This moral outrage helped pave the way for the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, which gave British police the power to shut down gatherings of 20 or more people where music was played that was “characterized by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” Other countries followed suit with similar laws to crack down on illicit raves.

Just imagine that a thousand years from now, the tabloid articles are the only written record of the raves. What would our descendants think? That ravers were dangerous? Possessed? Or, that the rave mania was a textbook case of mass hysteria? In fact, this is exactly what happened with the dancing plagues of the Middle Ages. All historical accounts were written by disapproving outsiders - priests and physicians like Paracelsus. We have no record from Frau Troffea or her fellow dancers. No firsthand accounts of why they danced.

We do know, however, why ravers raved.

Below is a fragment of the Ravers Manifesto written by an anonymous raver in 2000 that captures the spirit of the movement:

We were first drawn by the sound. From far away, the thunderous, muffled, echoing beat was comparable to a mother's heart soothing a child in her womb of concrete, steel, and electrical wiring. We were drawn back into this womb, and there, in the heat, dampness, and darkness of it, we came to accept that we are all the same. We came to accept that we are all equal. Not only to the darkness, and to ourselves, but to the very music slamming into us and passing through our souls: we are all equal. And somewhere around 35Hz we could feel the hand of God at our backs, pushing us forward, pushing us to push ourselves to strengthen our minds, our bodies, and our spirits. Pushing us to turn to the person beside us to join hands and uplift them by sharing the uncontrollable joy we felt from creating this magical bubble that can, for one evening, protect us from the horrors, atrocities, and pollution of the outside world. It is in that very instant with these initial realisations that each of us was truly born.17

The rave movement bloomed in the wake of the Cold War, carrying with it a new optimism, a yearning for community, and a hope for peace and freedom. On a rainy July 1st, 1989, just months before the Berlin Wall fell, the first Love Parade was held in West Berlin as a peace demonstration. Much to the surprise of the police, a group of 150 protesters were dancing ecstatically behind an old Volkswagen bus, instead of the usual rioting.18 In the months following the parade, the Cold War came to its anti-climactic ending. Forty years of stockpiling arms did not lead to an apocalyptic war, but instead, the Iron Curtain just crumbled down. Nobody had seen this coming. Nowhere was this more apparent and symbolic then in Berlin, where the wall had sharply divided East from West. When the wall came down in November 1989, it released decades of tension. Underground parties erupted all over Berlin with people dancing in empty warehouses, train stations and beer gardens. A new generation of East and West Germans danced together on a new music. Techno music became the voice of a new generation. Dancing into ecstasy, moved young people beyond their geographical identities and into an experience of oneness. Many young Germans first met people from ‘the other side’ during a rave, giving rise to the claim that Germany was first reunited on the dance floor.19 The need to dance, release, celebrate, and unite was so big that the Love Parade quickly swelled from its humble 150 dancers to 1.500 in 1990, and 15.000 in 1992, to a staggering 1.500.0000 in 1999, becoming the centerpiece of the global rave culture.

Raving Against the Machine

In Britain, the rave scene gave rise to a growing alternative youth movement. Grassroots rave organizers questioned and at times clashed with the political establishment. They did not organize for profit, but to celebrate freedom and inclusion in a time when Margaret Thatcher’s government destroyed community life and commodified public spaces. New Age Travelers roamed the country in buses and campervans, chasing festivals and a freer life. Ravers experienced alternate states of consciousness, spoke of universal love, and discovered spirituality to make sense of their ecstatic experiences. I was one of those young people.

One Sunday morning, after dancing well into the early hours, a group of us shuffled to someone’s place to crash. We were a ragtag group of worn-out ravers. The euphoria had long left our bodies, but we were still shimmering in its afterglow. As we walked homeward, we crossed a group of churchgoers. It was as if the veil between two parallel worlds had just lifted and for an instant, we both looked with mutual bewilderment at each other, each group convinced the others had lost their way.

As a former raver, I know I was neither possessed nor suffering from mass hysteria. Still, in hindsight, it feels as though a larger force – something older and wiser - moved through us, compelling thousands of young people to dance away in bliss in abandoned warehouses, desert plains, and moonlit beaches. Unwittingly, we had stumbled upon many of the same ingredients that trauma experts, like Bessel van der Kolk, recommend for healing: dancing, psychedelics, and community. These are the very elements that cultures across the world have used since time immemorial to transform grief and trauma. I believe this healing force moved not only through us as individuals, but also through the body of a wounded culture: calling us to remember our bond with the wild, to shake us out of our trance of consumerism, and to guide us back to community, ritual, and ecstasy.

Much of this disconnect comes from what Riane Eisler describes as the “dominator model”: a social system built on hierarchy, control, and the suppression of feeling, nature, and the feminine.20 Freud uncovered the dark side of this power-over model in the form of widespread abuse, but instead of criticizing the patriarchal system, he chose to reframe trauma as fantasy. Centuries earlier, Paracelsus also discounted Frau Troffea’s voice and accused her instead of feigning the dance affliction.

Why this hostility towards women?

Eisler explains that feminine values like compassion, sensuality and receptivity threaten hierarchical systems built on control, conquest, and competition. During the Victorian era the domination model was in full force. European and American imperialism was justified by ideologies as the White Man’s Burden, which framed colonization not as exploitation, but as a moral duty of white Europeans to “civilize” the “inferior” non-white peoples.21 Victorian masculinity was defined by control –control over women, over colonized people, and over one’s own emotions, passions and desires. But repressing basic human instincts does not make them disappear; they are driven underground, only to resurface as dark desires or inner demons. It’s not too far-fetched to see how a culture built on both external domination and internal suppression might fuel the very patterns of widespread sexual abuse it chooses to ignore.

Despite his reversal on trauma, Freud did help us understand how inner demons often get projected onto a marginalized group. The British tabloids certainly had a field day with the early raves. In reality, the dancefloors were, and still are, temporary refuges from a system of domination. On the floor power and vulnerability can dance together, as can sensuality and playful competition. Eisler calls this alternative the “partnership model”, rooted in reciprocity, co-creation, and reverence for life. The rave movement had its own credo for it: Peace, Love, Unity, and Respect or PLUR.

The contrast between the tabloid fearmongering and the raver’s credo couldn’t be starker. Could it be that the medieval dance maniacs were similarly misrepresented? Was Frau Troffea perhaps part of a group of medieval ravers? If so, what could be their credo or rallying cry?

Friskes!

The Dutch monk Petrus de Herenthal († 1390) describes how, around 1374, an unusual sect of men and women from various parts of Germany arrived in Aachen:

“Persons of both sexes were so tormented by the devil that in markets and churches, as well as in their own homes, they danced, held each others' hands and leaped high into the air. While they danced their minds were no longer clear, and they paid no heed to modesty though bystanders looked on. While they danced they called out names of demons, such as Friskes and others...”22

It is odd that Herenthal understood “Friskes” as the name of a demon. In fact, words like friskes, frisch, vrisch, frisk, or frisque appear in most German and Roman languages with related meanings: (a) to dance, frolic; (b) lively, brisk; and (c) fresh, new. All evoke a sense of vitality and the expression thereof: dancing.

It is possible the dancers were shouting out “Frisch” much like Flamenco dancers call out “Olé!” – a spontaneous expression of a powerful emotional or spiritual moment. Historian Max Dashu offers another perspective, proposing that Europeans may have revived trance dancing as a way of confronting the bubonic plague. She suggests that cries of “Friskes!” might have been invocations of healing power.23

This is a compelling possibility. After the fall of Rome, Europe went through a period of great migrations. In the centuries that followed, many people embarked on pilgrimages to their ancestral homelands, often blending Pagan and Christian traditions. Historian Louis Backman presents ample evidence that the 1374 dance mania was largely composed of Hungarian pilgrims, some returning to their roots, others joining in en route.24 Another clue suggesting the “frisk” dancing may have been an ecstatic dance revival lies in its timing: many outbreaks occurred around midsummer, a moment traditionally associated with pagan ring and bonfire dances, rituals of seasonal renewal, communal celebration, and honoring the life-giving Goddess.

At this point, it seems the dancing plagues reveal more about their chroniclers than the dancers themselves. We saw that when fear guides the pen, misunderstanding become a condemnation or a diagnosis. Modern scholars still rely on these biased historical sources, but nevertheless present their theories, like Mass Psychogenic Illness, with a voice of reason. However, as in Victorian times, power frequently disguises itself as reason and behind labels of hysteria or heresy often lies a deeper truth that challenges the established order. So, in closing, who was truly moved by their inner demons: the ecstatic dancers or the repulsed chroniclers? And who was gripped by mass hysteria, the ones dancing or the fearful onlookers who saw only a cesspool of sin?

Perhaps the real problem has never been the dancing itself, but the way we’ve come to view it.

Epilogue - Dionysus’ Daughters: Isadora and Gabrielle

The Ravers Manifesto compares the rave to a womb where dancers can be reborn. But rebirth doesn’t happen by staying in the comfort of the womb. To find ecstasy, we must cross the threshold of the known and enter the dark forest, where bliss awaits, but also danger. This is where our inner demons test us and can tear apart our long-held beliefs. Across cultures and time, people have developed rituals and appointed guides, like elders or shamans, to help navigate this sacred and treacherous terrain.

Unfortunately, my fellow ravers and I had no such guidance. There was no safe container, no map. And while some of us found healing amidst the pumping beats, others got lost. While I’m reluctant of echoing the tabloids’ hysteria, a few of my friends did end up in psychiatric wards.

Ravers weren’t the only ones dancing toward ecstasy. In dance studios and gym halls, Conscious Dance practices also began to blossom, seeded by the courageous work of defiant dance innovators who challenged the rigid norms of movement and society.

Repression often breeds rebellion. And in the twilight of the Victorian era, one extraordinary rebel rose to the stage: Isadora Duncan. A visionary dancer, Duncan cast off the corset and pointe shoes of classical ballet and danced barefoot, hair unbound and dressed in flowing tunics inspired by ancient Greek art. Isadora embraced natural movement, like running and skipping, welcoming emotional expression and breath. She reclaimed the divine feminine and famously said:

“You were once wild here. Don’t let them tame you.”

Isadora Duncan saw wild ecstasy in ancient Greek sculptures and brought it to life on stage. Her art, said Isadora, symbolized women’s liberation from “hidebound conventions.”25 Audiences were mesmerized by her unapologetically fierce and feminine presence. The Goddess had returned.

Today, the freedom to move spontaneously and naturally is often taken for granted on the ecstatic dancefloor. But it took dancing rebels, like Isadora Duncan, to free the (female) body of its literal and metaphorical corset. Isadora paved the way for other pioneers, like Martha Graham, who further shaped contemporary dance. From the 1950’s onward, these new ways of moving crossed with therapeutic models, giving rise to Conscious Dance practices, like Authentic Movement, Contact Improvisation, Continuum Movement, and the 5Rhythms. And that brings us back to an unwilling character in this story: Sigmund Freud.

In 1936, Sigmund Freud snubbed an ambitious psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, who had travelled from South Africa to meet him in Vienna. The psychiatrist, Frits Perls, had fled to South Africa with his wife Laura, after Hitler’s rise to power. There, the couple developed ideas that challenged Freudian orthodoxy, which Perls was eager to share. But Freud, unimpressed, dismissed them. Disillusioned, Perls broke away from psychoanalysis and began developing what would become Gestalt Therapy. At its core, Gestalt therapy invites people to become fully present and aware of their emotions, bodily sensations, and thoughts. Perls’ bold style of therapy exposed the internalized voices of the dominator culture and helped clients reclaim their disowned parts and take ownership of their lives.

In the 1960s, Perls became a key figure at the Esalen Institute. There, he collaborated with mind-body innovators like Ida Rolf, founder of Rolfing. He also met with a young dancer who came to Esalen in search of a new direction after her dance ambitions were crushed by a knee injury. Her name was Gabrielle Roth. Perls invited Gabrielle to offer movement classes for his Gestalt Therapy group. This led her to become the movement specialist in Esalen, offering movement classes to thousands of seekers in the 60’s.

Within the creative and spiritual breeding ground of Esalen, Gabrielle Roth birthed her own brand of Ecstatic Dance. Drawing from Gestalt therapy practice, Shamanism and Native American spirituality, she developed her healing maps to ecstasy.26 This movement map, later known as the 5Rhythms, would influence many of today’s Conscious Dance practices, such as Soul Motion, Movement Medicine, Open Floor, and Ecstatic Dance. I was fortunate enough to study with Gabrielle and eventually became a 5Rhythms teacher myself – learning and later teaching the maps to ecstasy that I lacked as a teenage raver.

Both Isadora Duncan and Gabrielle Roth were instrumental in reviving the sacredness of dance in the West. In their search for ecstasy both drew, in part, on European sources: one from ancient Greece, the other from modern psychotherapy. Which raises the question: what happened in between?

Well, the dancing plagues, and centuries of suppression of Europe’s ecstatic traditions and feminine spheres of power. That suppression runs so deep that many European descendants now carry what IFS therapy calls legacy burdens– the emotional, psychological or behavioral patterns that are passed down through the generations.27 These burdens show up as shame, fear, or self-censorship.

How many people only dare to dance after drinking alcohol? How many men are afraid to appear emasculated if they move with sensitivity? How many women reign in their sensuality while dancing, afraid to appear “too much” or afraid to give “the wrong impression”?

Before these burdens can be healed, they must be identified and traced to their origins. For that, we need to face our forgotten history, buried somewhere between ancient Greek rites and the birth of psychotherapy.

Join me soon for Part II of this essay on The Dancing Plagues, where we will delve deeper into the pagan traditions and ecstatic dances of old Europe.

If you have listened to this essay, be sure to also check out the footnotes.

Saint Vitus was a Christian martyr from the 4th century who, over time, became the patron saint of dancers, actors, epileptics, and those suffering from neurological movement disorders.

As Louis Backman notes in “Religious Dances” (p.278), the color red has carried significance since antiquity. Greeks and Romans wore a red thread around their neck for protection. Christians adopted the color to symbolize both the Devil as holy blood. Red could drive out demons but also carry a curse. In Hans Andersen’s fairy tale “The Red Shoes” a girl starts to dance uncontrollably after putting them on, until her feet are cut off to break the spell.

Other terms that are used are Saint Vitus Dance and Choreomania. Choreo- originating from χορός (choros), meaning "dance" and μανία (mania) meaning "madness" or "frenzy".

See the “Four treatises of Theophrastus von Hohenheim, called Paracelsus” Page 158.

See Paracelsus’s writing: Opus Paramirum

Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493–1541) named himself Paracelsus, possibly to express that he would surpass (Para) the 1st century Roman medical authority Aulus Cornelius Celsus. However, he was still also a man of his time and also wrote a treatise on elemental beings, like nymphs.

This theory was first put forward by Louis Backman in his 1952 book “Religious Dances”, who suspected an infection by the Claviceps purpurea fungus.

Moreover, similar dance mania’s have not been reported after ergot poisoning in other parts of the world.

See Barbara Ehrenreich’s book: Dancing in the Streets.

Ehrenreich writes this quote comes from The Drums of Winter (a documentary film by Sarah Elder and Leonard Kamerling), University of Alaska Museum, Fairbanks, Alaska, 1988.

The Myal dance is a traditional Afro-Jamaican ritual dance that originated among enslaved Africans in Jamaica during the colonial period. It is deeply rooted in West African spiritual practices, where dancers become possessed by ancestral spirits who speak or act through them. Later Myal dances merged with Christianity.

As an interesting sidenote, one of the treatments of hysteria supposedly was a genital massage with a new medical instrument called the vibrator. There is, however, still a scientific debate going on whether this was the case at all, or how frequent this happened.

See here for the interview with Bessel van der Kolk.

Mind you, this was still the pre-mobile phone era when people gathered by word of mouth and flyers.

See the work of Neuropsychopharmacology Professor David Nutt: Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. The Lancet, Volume 376, Issue 9752, 1558 - 1565

The Sun, 19 October 1988, column: “Don’t be a Sucker”.

See “The Chalice & the Blade” by Riane Eisler.

The White Man’s Burden (1899) was a poem by Rudyard Kipling about the Philippine-American War, encouraging and justifying the colonization of the Philippine Islands.

In Religious Dances by Louis Backman page 191.

See: The Midsummer Dances by Max Dashu.

See Religious Dances by Louis Backman page 230.

See Isadora Duncan’s book “My Life” page xi.

Maps to Ecstasy is also the title of one of the books written by Roth. It carries the subtitle: a healing journey for the untamed spirit - perhaps a nod to Isadora Duncan?

Thank you Léon! I can read this anytime I forget the meaning and purpose of what I’m doing with Ecstatic Dance.

What a beautiful reminder of what dance and movement can do for us! Beautifully written and I could feel the truth underneath your words. I felt touched in many ways and moments, thank you Leon! Your text inspired me to remember again and again my love for dance, for movement, for the deep wisdom our bodies carry from many generations even, the healing power and the power to connect us all with our essence. ❤️❤️